The Deep Rear Is Dead – Long Live the Deep Rear: Pavutyna FPV Swarms vs Russian Bombers

Proximity Doctrine & Ukraine’s AI-Guided FPV Swarms Against Russia’s Bomber Fleet — Operatsija “Pavutyna” (Spider’s Web)

On June 1, 2025, Ukraine’s SBU launched its boldest drone operation yet—targeting Russia’s long-range bomber fleet deep inside Russian territory. Codenamed “Spider Web” (Ukrainian: Операція «Павутина», Operatsija "Pavutyna"), the strike used container-mounted drones hidden in civilian trucks to hit four airbases simultaneously, destroying at least 8 Tu-95s and 4 Tu-22M3s, with possible additional damage

The geographic assumptions of rear-area immunity are dead.

Ukraine just proved it.

The future of strategic warfare belongs to cheap, autonomous, near-field systems—not distant platforms.

The “deep rear” still exists—but now it lives in design, denial, dispersion, not in distance.

This grosswald.org briefing provides a granular, expert-level breakdown of the operation—Russia’s largest strategic aviation loss since the Cold War. Drawing on OSINT, satellite data, insider leaks, and official statements, the report reconstructs the timeline, military strike profiles, and intelligence ecosystem behind the assault.

Contents include:

- Chronological timeline and strike maps across all affected airfields

- Analysis of Ukrainian tactics, SBU logistics, and launch mechanisms

- Confirmed equipment losses (Tu-95, Tu-22M3) and defensive system bypass

- Doctrinal implications for Russian strategic deterrence and escalation posture

- Full inventory of Ukrainian and Russian systems involved (drones, radars, EW)

Kyiv, 01 June 2025 - On the 29th anniversary of Ukraine surrendering its last nuclear weapons to Russia, Kyiv launched what may be the most successful sabotage operation of the war to date: a drone strike deep into Russian territory, targeting the very aircraft once responsible for delivering Soviet nuclear payloads.

Codenamed Operation Spider's Web (Ukrainian: Операція «Павутина», Operatsija "Pavutyna"), the attack involved a year-long covert build-up and culminated in an unprecedented multi-axis strike on four Russian airbases—Olenya (Murmansk), Belaya (Irkutsk), Shaykovka (Kaluga), and Ivanovo (northeast of Moscow)—with reports of a possible fifth location in Amur.

Großwald | Doctrinal Frame & Why it Matters: With no Western involvement, Ukraine has disabled or destroyed an estimated 20–34% of Russia’s active strategic bomber force in a single coordinated strike—using covertly deployed, low-cost drone swarms. The operation marks a doctrinal break: deep strikes no longer depend on range, but on infiltration, autonomy, and civil disguise.

- Deep-airbase deterrence is obsolete. Ukraine showed strategic bombers can be hit anywhere; fixed basing is now globally at risk.

- Perimeter gaps, not SAM failure, enable strikes. Traditional air defense can't stop proximate, low-signature threats.

- Nuclear signaling is weakened by visible exposure. Dual-use bomber vulnerability erodes strategic credibility.

- AI-driven sabotage is now a proven capability. Ukraine has scaled autonomous drone strikes for strategic effect.

- Defense must evolve beyond AD bubbles. Dispersion, deception, and logistical denial are now essential.

If Ukraine’s claims prove accurate, Russia has lost one-third of its strategic airborne delivery capacity in a single operation.

The attack will likely enter the doctrinal pantheon of strategic airpower disruptions—alongside Taranto (1940), Pearl Harbor (1941), and Osirak (1981). Not for its scale, but for its doctrinal breakthrough: Operation Spider’s Web marks the first large-scale execution of a Proximity Strike Doctrine.

In this model, the decisive variable is no longer distance, but proximity and deniability. Strategic aviation, once presumed safe behind the lines, is now a frontline target.

Proximity Strike Doctrine (PSD) — first demonstrated at scale during Ukraine’s Operation Spider’s Web, PSD refers to the covert deployment of short-range tactical drones from inside enemy territory to achieve strategic effects. Unlike traditional long-range strikes, PSD relies on infiltration, civil disguise, and distributed autonomous delivery to bypass air defenses and target high-value assets.

Quick View: 'SBU Operation Spider’s Web'

Ukrainian SBU deep-strike drone operation, June 1, 2025

Strike Methodology:

Civilian trucks disguised as mobile cabins launched 117 FPV drones from within Russia, bypassing radar and traditional SAM defenses. Launch points were positioned 1–7 km from target bases.

Airbases Hit:

Olenya (Murmansk), Belaya (Irkutsk), Ivanovo-Severny (AWACS), Dyagilevo (Ryazan). Attempted strikes in Amur and near Moscow (Voskresensk) were likely intercepted or preempted.

Targeting System:

Drones employed AI-based silhouette recognition, likely trained on public imagery of Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3. Control links used GSM networks and autonomous modes to minimize latency.

Ukrainian Claims:

41 aircraft hit; $7B in damage; 34% of Russia’s strategic bomber force disabled. Claims partially corroborated by OSINT satellite imagery and video footage.

Russian Acknowledgment:

MoD confirmed “multiple aircraft fires” at Olenya and Belaya. Milbloggers called it “Russia’s Pearl Harbor.” Retaliatory planning underway.

- 8x Tu-95MS “Bear-H” (4 at Olenya, 4 at Belaya)

- 4x Tu-22M3 “Backfire-C” (Belaya)

- 1x An-12 transport (Olenya)

- ≥3 hardened shelters breached (Belaya)

Doctrinal Impact

- Strategic deterrent basing doctrine compromised

- Proof-of-concept for low-cost deep strikes

- First confirmed AI-targeted drone swarm use

- Operational without Western systems

While the quick view above outlines the immediate operational picture, the full implications of Operation Spider’s Web—on Russia’s nuclear posture, base doctrine, escalation thresholds, and military psychology—are unpacked in detail further below. Scroll to the “Strategic and Doctrinal Context” section for in-depth analysis.

Timeline of the June 1, 2025 Strike(s)

May 31, 2025 (Operation Eve):

Ukrainian SBU (Security Service) special operators finalize preparations for a coordinated attack on Russian bomber bases. Dozens of drones and launch equipment are positioned covertly near multiple airfields. President Zelensky and SBU chief Vasyl Maliuk personally supervise the operation’s final stages. All Ukrainian operatives are secretly exfiltrated from Russia on the eve of the attack to ensure their safety.

Early June 1, 2025 (Pre-dawn):

In a near-simultaneous strike across several time zones, Ukrainian drones launch from hidden sites adjacent to at least four Russian military airbases. At approximately 06:00 Moscow time, witnesses in the Murmansk region report explosions and large fires at Olenya (Olenegorsk) Airbase, a strategic bomber base on the Kola Peninsula. Almost concurrently, in eastern Siberia, locals near Belaya Airbase (Irkutsk region) observe drones buzzing overhead and massive blasts; Belaya’s residents record video of drones launched from a truck and smoke rising from the base. Dyagilevo Airbase (Ryazan Oblast, central Russia) and Ivanovo-Severny Airbase (Ivanovo Oblast, northeast of Moscow) are also targeted by drone swarms around the same time. Russian forces at some sites appear caught off guard – at Olenya, civilians even filmed a truck parked near a gas station launching drones toward the airfield moments before fireballs erupted.

Morning June 1 (Initial Russian Response):

Regional authorities and media begin acknowledging the attacks. Igor Kobzev, governor of Irkutsk, confirms a drone strike at a “military unit” near the village of Sredny (the vicinity of Belaya Airbase) and notes the drones were launched from the back of a truck nearby. In the Arctic, residents of Olenegorsk and satellite towns share footage of thick black smoke billowing from Olenya Airbase. Russia’s air defenses around Ivanovo and Ryazan claim to have intercepted or jammed drones before they reached those bases. The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) announces that in five regions (Murmansk, Irkutsk, Ivanovo, Ryazan, and Amur) a “terrorist attack using FPV drones” was attempted, but alleges that in three regions (Ivanovo, Ryazan, Amur) the attacks were repelled. However, the MoD concedes that “several units of aircraft caught fire” at the Olenya and Belaya bases in Murmansk and Irkutsk. They report no personnel casualties, and claim some perpetrators (suspected saboteurs on Russian soil) have been detained by authorities.

Mid-day June 1 (Containment and Alerts):

Russian emergency crews at Olenya and Belaya work to extinguish the aircraft fires and secure the sites. By early afternoon, Russia declares the fires under control and an investigation underway. Fearing further attacks, emergency air-defense alerts are declared at other strategic airbases: notably Engels (Saratov Oblast, main bomber base) and Morozovsk (Rostov Oblast) are put on heightened alert due to a “possible air threat”. This suggests Russian command is unsure if more drone teams lurk elsewhere. Meanwhile, unconfirmed reports emerge of a fifth drone launch truck found near an airfield in Voskresensk (Moscow Oblast) – possibly indicating an attempted strike on a Moscow-area base, which was disrupted before it could cause damage. (Some ambiguity remains whether this was a separate target or confusion with the other attacks.)

Afternoon June 1 (Ukrainian Disclosure):

Ukraine’s SBU publicly acknowledges it orchestrated the operation, codenamed “Pavutyna” (Spider’s Web). Senior officials boast that the drone strikes hit 41 Russian military aircraft across the multiple airfields. The SBU estimates the damage to Russia’s strategic aviation at $7 billion USD. In a Telegram statement, the agency asserts that “34% of [Russia’s] strategic cruise missile carriers” – roughly one-third of Russia’s bomber fleet – have been put out of action. These claims, while bold, are later partially supported by satellite imagery (see OSINT analysis below). Ukrainian media and officials begin referring to the operation as the largest single-day strike on Russian territory since the war began.

Evening June 1 (Official Statements):

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky praises the strike in his nightly address, calling it an “absolutely brilliant outcome” for Ukraine. He confirms that 117 drones were used in the operation, emphasizing that this longest-range Ukrainian strike ever was planned over a year and a half in advance. Zelensky notes that the feat was achieved independently by Ukraine (a subtle point that no Western weapons were directly involved). He also reveals that Ukrainian intelligence set up a forward control post “right next to a regional office” of Russia’s own FSB security service during the operation – underscoring how deeply SBU agents infiltrated Russian territory.

June 2–3, 2025 (Aftermath):

As smoke clears, independent analysts begin assessing the damage via satellite. OSINT imagery emerges confirming multiple destroyed bombers (details below). Russian officials maintain a terse stance, condemning the “terrorist drone attacks” and vowing retribution, but still not fully detailing the extent of losses. Peace talks in Istanbul that were scheduled for June 2 proceed with a tense atmosphere; Ukraine arrives having dealt Moscow a stark blow on the eve of negotiations.

Strike Execution: Drones, Tactics, and Scale of Attack

Ukraine’s Operation “Spider’s Web” introduced an ingenious “Trojan Truck” tactic to deliver explosive drones to high-value targets thousands of kilometers inside Russia. Instead of launching UAVs from Ukrainian territory (which would be impractical given distances of 1,800–4,300 km), the SBU smuggled drones deep into Russia and positioned them right near the target bases. According to Ukrainian officials, the drones were concealed in wooden shed-like structures mounted on trucks, resembling ordinary mobile cabins.

These improvised launch vehicles were driven to spots just outside the airbases – in one case, parked at a gas station along the main road by Olenegorsk, only ~6–7 km from the Olenya bomber base. At the chosen moment, remotely triggered mechanisms lifted the shed roofs, allowing the drones to take off directly from the truck beds and swarm toward their targets. This method allowed the attack drones to bypass Russia’s traditional early-warning systems by originating from point-blank range.

Each launch truck carried a swarm of small FPV (First Person View) drones – essentially hobbyist-style quadcopter or loitering drones outfitted with explosives and cameras. Photos later shared by the SBU show dozens of identical black quadcopter drones stacked in a warehouse, purportedly the same models used in the strikes. The operation involved 117 drones in total, distributed among several teams, indicating each target base may have been attacked by a salvo of dozens of drones simultaneously. This sheer number ensured that even if some drones were jammed or shot down, many would get through. It was the largest drone strike of the war to date by scale.

Once deployed, the drones flew low (nap-of-the-earth) and directly toward parked aircraft. Their small size and low altitude meant they could evade or confuse radar and slip underneath the coverage of long-range SAM systems. Russian S-400 and S-300 surface-to-air missile batteries, which defend these bases against cruise missiles and aircraft, were largely ineffective against slow, low, small drones coming from just outside the perimeter. Pantsir-S1 short-range defense units (if present) also struggled to detect and engage the swarming drones in time. In essence, Ukraine exploited a seam in Russia’s air defense: the gap between perimeter ground security and the national air-defense network.

A Ukrainian military source described the drones used as FPV kamikaze drones with AI-driven guidance – reportedly trained to recognize the silhouette of Russian bombers. This suggests some drones might have had autonomous target-recognition to home in on aircraft, though human operators likely guided many of them via live video feed for precision. According to footage and damage patterns, the drones aimed for the fuel-laden wing and engine areas of the bombers to ensure catastrophic fires, rather than just piercing the fuselage. This tactic paid off: multiple struck bombers burst into flames and exploded due to fuel detonations, rather than simply incurring localized damage.

Importantly, the attack was coordinated across multiple fronts. Ukrainian intelligence had to synchronize teams in far-separated regions (the distances between some targeted bases were over 4,000 km) and likely chose a simultaneous or near-simultaneous strike window to maximize shock and confusion. The SBU later revealed the operation took over 18 months of preparation – involving recruiting or inserting agents in Russia, transporting the drones and launch equipment clandestinely, and conducting reconnaissance to pick launch sites with clear lines-of-fire to parked aircraft.

The audacity of hiding launch teams “in plain sight” (e.g. next to a highway or village near a base) was matched by solid OPSEC: Russian security services were apparently unaware of the preparations until the drones were in the air. In a pointed detail, President Zelensky noted that the command-and-control center for the operation was set up right under the nose of Russia’s FSB, in a location adjacent to an FSB office in Russia.

Overall, Operation Pavutyna leveraged inexpensive drones (often costing only a few thousand dollars each) to destroy assets worth many millions apiece. It demonstrated a new paradigm of asymmetric warfare: by using creative delivery methods and massed drone swarms, Ukraine neutralized some of Russia’s most valuable military planes without using any fighter jets or long-range missiles.The scale and precision of the strike deep inside Russia marks a tactical inflection point — not just an escalation, but a doctrinal shift now under close scrutiny by military analysts worldwide.

Affected Russian Airbases and Damage Assessment

The June 1st strikes targeted five locations across Russia (four confirmed airbases and one reported attempt near Moscow). Below we detail each location, the military assets stationed there, and the extent of confirmed damage. The focus of the drones was on aircraft – particularly long-range bombers that Russia has used to launch cruise missiles at Ukraine – but we also note impacts on air defense systems and infrastructure where applicable.

Olenya Airbase (Murmansk Oblast, Arctic Kola Peninsula)

Role & Units - Olenya: Olenya (also known by its Soviet name “Olenegorsk”) is a remote Arctic airbase about 90 km south of Murmansk. Since late 2022 it has served as a dispersal field for Russia’s Long-Range Aviation – hosting strategic bombers that were moved away from vulnerable main bases.

Prior to the attack, satellite imagery showed Tu-95MS “Bear-H” propeller strategic bombers at Olenya, and reportedly some Tu-22M3 “Backfire-C” medium bombers as well. (Some Tu-160 “Blackjack” strategic bombers were also observed at Olenya in past months, though it’s unclear if any were present in June.)

Attack Outcome - Olenya: The drone strike on Olenya was devastatingly effective. Multiple FPV drones hit the southern parking apron, where a number of Tu-95MS were sitting out in the open. Video released by Ukraine’s SBU (and geo-located to Olenegorsk) shows at least four Tu-95MS bombers engulfed in flames on the tarmac, one after the other, with secondary explosions visible. In addition, a smaller propeller-driven plane near them – identified as an An-12 military transport aircraft – was seen burning intensely. By the time the fires were out, the OSINT consensus is that four Tu-95MS “Bear” bombers were destroyed at Olenya, along with the An-12 transport. Another Tu-95 was partially on fire in the video; if that aircraft survived at all, it likely suffered heavy damage.

Essentially, every bomber that was parked on that apron was knocked out. Ukrainian sources claimed additional aircraft at Olenya were damaged, though imagery confirms the destruction of four bears as the primary result. The photo below, taken from strike footage, shows the scene of destruction:

Figure: Still frame from a strike video of the Olenya Airbase attack in Murmansk Oblast. Multiple Tu-95MS “Bear”strategic bombers can be seen ablaze on the parking apron after being struck by explosive drones. The video (released by Ukrainian special forces) shows at least four Tu-95MS bombers burning, with one An-12 turboprop transport also on fire (left). This image captures the moment the Ukrainian drones devastated Russia’s Arctic bomber dispersal site.

Surviving Assets - Olenya: The strike likely destroyed the majority of bombers that were forward-deployed at Olenya. Any remaining intact aircraft would have been those not on the apron at the time – for example, if any Tu-95 or Tu-160 had departed earlier or were in hangars (Olenya has limited shelter facilities). As of early June, no Tu-160 losses have been reported, suggesting that either none were present or they escaped damage. Russia still controls Olenya Airbase, so any surviving bombers were probably evacuated to safer locations immediately after the attack. The loss of four Tu-95MS is highly significant – these represented a substantial portion of Russia’s available Kh-55/101 cruise missile carriers. (For context, Russia’s active Tu-95MS fleet before this strike was on the order of only a few dozen aircraft.)

Air Defense & Infrastructure - Olenya: Despite housing valuable assets, Olenya’s air defense failed completely to stop the drones. The base is in a region covered by some of Russia’s most advanced systems (the Kola Peninsula hosts layered defenses to protect the Northern Fleet and strategic forces). It’s likely that an S-400 SAM battery and Pantsir-S1 short-range systems were assigned to guard the area. However, the low-flying quadcopters went undetected by radar, and by launching from just outside the base, they rendered long-range SAMs irrelevant. There are unconfirmed reports that a Pantsir unit at Olenegorsk opened fire after the explosions began, but far too late to intercept the inbound drones.

In terms of infrastructure, the attack was surgical: it did not crater runways or blow up fuel depots (no major secondary blasts were noted aside from the burning planes’ fuel). The drones’ small warheads were enough to destroy aircraft but not designed for large structural damage. Thus, the airfield itself remains usable – indeed, Russian emergency response likely focused on clearing debris and repairing any scorched pavement once the fires were out. The psychological impact, however, on the security of this once “safe” Arctic base is incalculable.

Belaya Airbase (Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia)

Role & Units - Belaya: Belaya Airbase (near Usolye-Sibirskoye in Irkutsk Oblast) is a key facility for Russia’s Long-Range Aviation in the eastern part of the country. It traditionally hosts the 184th Heavy Bomber Regimentflying Tu-22M3 “Backfire-C” bombers – used in conventional strikes and capable of carrying Kh-22/32 missiles. In recent months, Russia had also re-deployed some Tu-95MS “Bear” bombers to Belaya (likely to put them out of reach of earlier Ukrainian attacks in western Russia). Reports indicate several Tu-95MS and even Tu-160 were occasionally at Belaya before the strike. The base is over 4,300 km from Ukraine – so far that Ukrainian drones had never struck this region before.

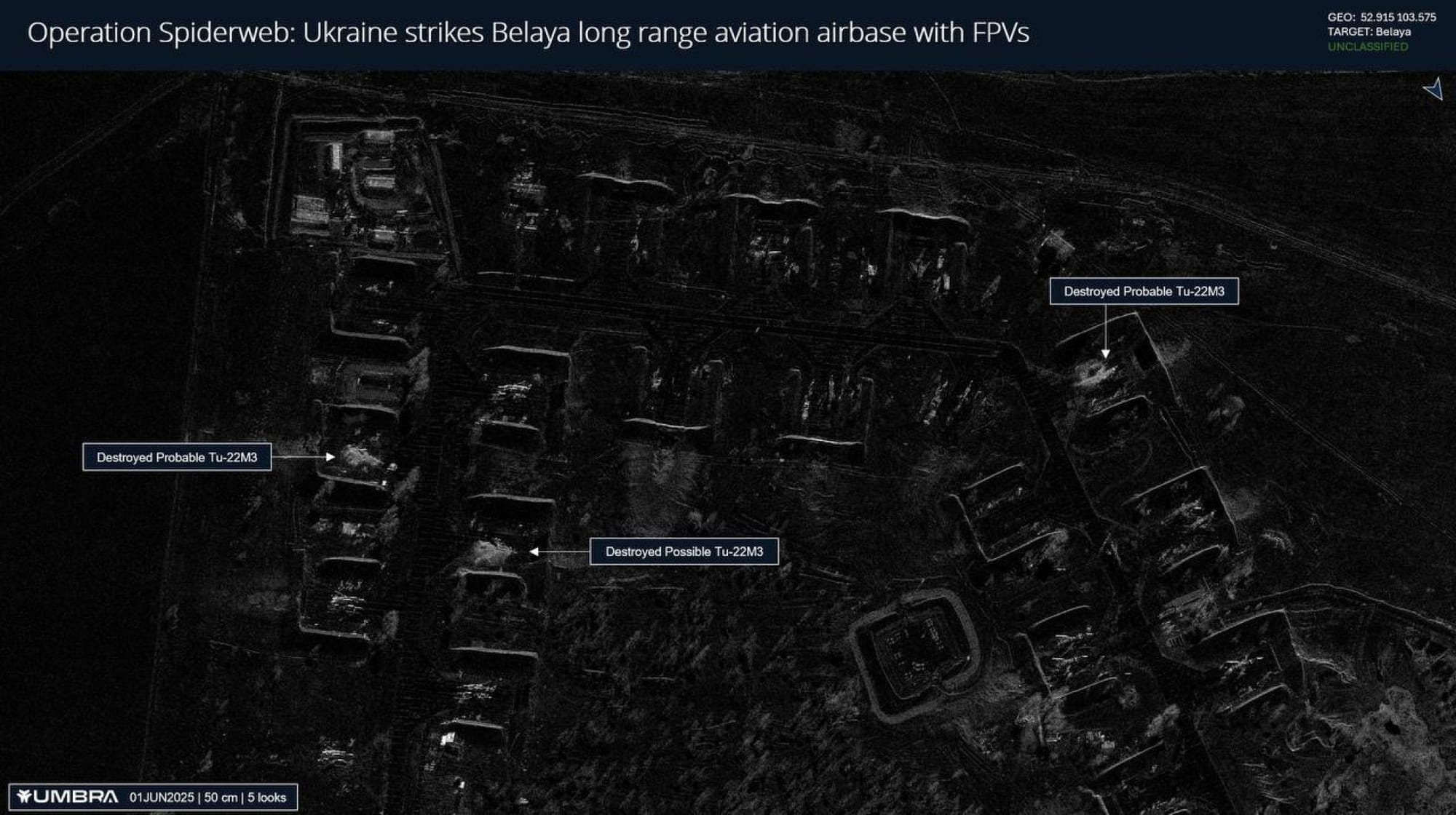

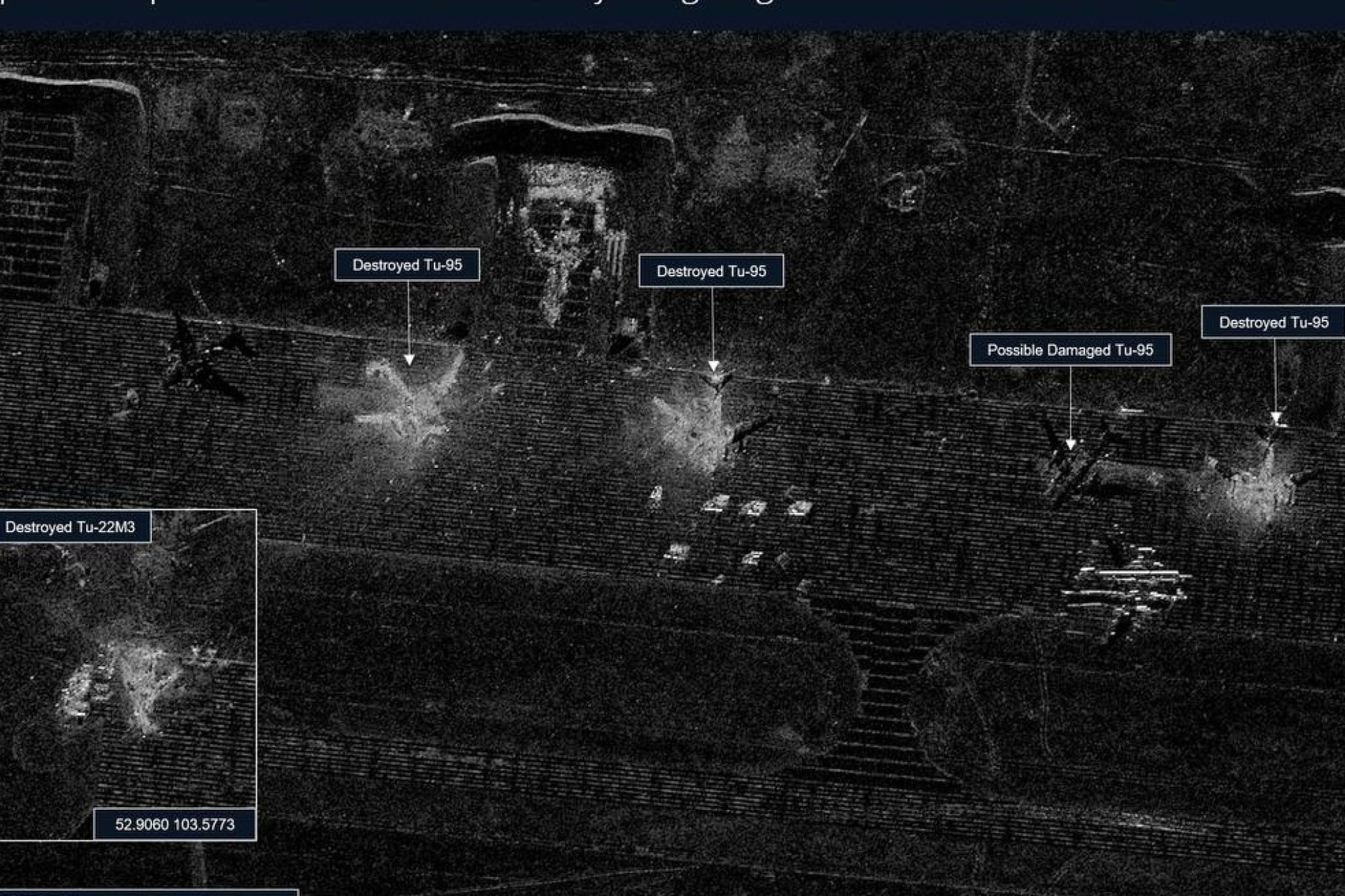

Attack Outcome - Belaya: The destruction at Belaya was extensive – it appears to be the hardest-hit of all targeted bases. Ukrainian drones penetrated the base and struck bombers parked both in the open and in partially hardened shelters. Because Belaya is a more permanent base, some of its bombers were stored in concrete revetments or shelters. In the aftermath, high-resolution satellite imagery (including synthetic aperture radar images) was obtained by OSINT analysts, which conclusively showed multiple destroyed aircraft. According to independent analysis of imagery by Umbra and others, at least 8 bombers were destroyed at Belaya. This includes four Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers and four Tu-95MS Bear bombers. Notably, three of the Tu-22M3s were inside “hardened” aircraft shelters – yet they were still obliterated, leaving large debris fields visible even via radar imaging. The drones were able to fly into or near the entrances of these shelters and detonate, showing that even semi-fortified hangars did not prevent damage. On the open tarmac, at least three Tu-95MS were gutted by fire/explosions, and another Tu-95 was heavily scorched (possibly repairable, but out of action for now). Russian officials have been tight-lipped, but local videos on June 1 showed massive fires and secondary blasts at Belaya, confirming the visual evidence of multiple bombers on fire. In total, Belaya lost roughly a squadron’s worth of bombers in this single strike – a major blow to Russia’s eastern bomber force. The following SAR satellite image analysis highlights the damage:

Figure: SAR satellite imagery of Belaya Airbase in Irkutsk Oblast (captured June 2, 2025) showing destroyed Russian bombers. Analysts have annotated several blast sites. Notably, four Tu-22M3 “Backfire” bombers (circled in annotation) were destroyed even inside their open-ended concrete shelters. On the parking ramp at right, at least three Tu-95MS “Bear” bombers were also destroyed or heavily damaged by drone strikes. This imagery, provided by Umbra Space and OSINT / Chris Biggers, confirms the scale of destruction inflicted at Belaya.

Surviving Assets - Belaya: Belaya Airbase likely had more aircraft on site than those destroyed – possibly additional Tu-22M3s that were parked elsewhere or undergoing maintenance. Those not caught in the blasts could be considered “survivors,” and Russian forces presumably scrambled to disperse any remaining bombers after the attack. Still, losing four Backfires is significant; it’s estimated Russia had only around 60-70 Tu-22M3 in service, and production of this model ceased decades ago. The Tu-95 losses at Belaya (4 confirmed destroyed, 1 damaged) are equally critical: Tu-95MS are limited assets (roughly 40-50 in active service pre-war), and they form a core part of Russia’s nuclear and conventional long-range strike capability. Any Tu-95s that survived at Belaya may have been flown out to the Far East or back west to Engels after the incident. The operational tempo at Belaya is likely curtailed for now, as the unit assesses its losses. There’s also the practical matter of clearing wreckage: two or three parking spots and possibly the taxiway are filled with burned-out hulks that will need heavy equipment to remove.

Air Defense & Infrastructure - Belaya: Belaya, despite its remote location, had some air defenses – possibly older S-300PS batteries protecting the Irkutsk region and local short-range systems. The Irkutsk governor’s statement that drones launched from a nearby truck suggests that base perimeter security was the weak point. There is no evidence that any Russian SAMs managed to engage the drones over Belaya; the attack likely happened too quickly for a coordinated response. By the time alarms sounded, drones were already impacting aircraft. The infrastructure at Belaya sustained collateral damage: at least one hardened aircraft shelter was blown apart (those will require rebuilding), and the tarmac in some areas was scarred by explosions. However, the runway was not targeted and remained intact. Indeed, on June 2, Russian sources claimed that the airfield was operational again, with unaffected aircraft being relocated. The attack starkly exposed that Belaya’s lack of extensive hardened shelters (only a few exist, and even those were compromised) made its bombers easy prey – something Russian commentators lamented after the fact.

Dyagilevo Airbase (Ryazan Oblast, Western Russia)

Role & Units - Dyagilevo: Dyagilevo is a major long-range aviation base located near Ryazan, about 200 km southeast of Moscow. It houses elements of Russia’s Ryazan Aviation Regiment, including Tu-22M3 bombers and Il-78 “Midas” aerial refueling tankers. Notably, Dyagilevo was one of the bases hit by Ukrainian drone strikes in December 2022 (that attack damaged a Tu-22M3). It’s also historically a training base for bomber crews. Given its relative proximity to Ukraine compared to the other targets, Dyagilevo’s defenses were likely on higher alert.

Attack Outcome - Dyagilevo: In the early hours of June 1, Ukrainian drones also targeted Dyagilevo. Russian MoD statements claim that the attack on this base was fully repelled – i.e., that air defenses shot down the incoming drones and no damage was incurred. Independent verification is limited: unlike Olenya and Belaya, no photos or videos have surfaced showing explosions at Dyagilevo on that day. It’s plausible that Russian short-range defenses (perhaps Pantsir systems or even small arms) managed to destroy the drones before they reached the parked aircraft. The absence of visual evidence of fires suggests Dyagilevo emerged unscathed in terms of hardware losses. However, one must treat Russian claims with caution – it is possible minor damage occurred (e.g., a drone might have detonated near a plane causing shrapnel holes) that was not admitted. As of now, no Tu-22M3 or Il-78 losses at Ryazan have been reported. This indicates the drones either failed to hit their targets or were neutralized.

Surviving Assets - Dyagilevo: All of Dyagilevo’s bomber and tanker fleet is presumed to have survived the June 1 attack. If any drones did get through, the damage was not significant enough for OSINT to detect. Thus, the base likely retains its full complement of Tu-22M3s (dozens) and tankers. After the attack, Russia would undoubtedly reposition some assets – possibly moving bombers further from Ukraine or to civilian airfields temporarily – to reduce concentration at Dyagilevo. The earlier December 2022 drone strike had already proven Dyagilevo was within Ukraine’s reach (using longer-range drones), so by 2025 the base was partially hardened (there were reports of bombers being spaced out or moved). Surviving aircraft could resume operations quickly, as the base’s runway and fuel infrastructure were untouched on June 1.

Air Defense & Infrastructure - Dyagilevo: Given the previous attack, Dyagilevo was likely equipped with additional point-defense systems. Reports prior to this strike indicated Russia positioned Pantsir-S1 gun-missile systems and perhaps electronic warfare units around key bases like Dyagilevo to counter drones. These measures may have paid off here. The MoD explicitly said “attacks were repelled” at Ryazan region airfields, implying some defensive success. It’s worth noting that Moscow’s integrated air defense network extends over Ryazan – meaning medium-range SAM sites in the Moscow region could have been cued to potential threats. However, since Ukraine’s drones were launched from very close range, larger SAMs would have had virtually no reaction time. The likely hero of Dyagilevo’s defense, if any, was the human factor – sentries spotting drones or rapid-fire AA guns engaging them. No infrastructure damage has been reported at Dyagilevo. The base remained on heightened alert after, and Russian engineers likely began improving drone defenses (e.g., installing more surveillance cameras, lighting, and perhaps physical barriers around the perimeter) in response.

Ivanovo-Severny Airbase (Ivanovo Oblast, Central Russia)

Role & Units - Ivanovo-Severny: Ivanovo-Severny is an airfield in Ivanovo Oblast (approximately 250 km northeast of Moscow). It is best known as a base for Russia’s A-50U “Mainstay” Airborne Early Warning & Control (AWACS) aircraft. These AWACS planes (analogous to the US E-3 Sentry) are critical for long-range radar coverage and coordinating Russian air operations. Ivanovo has also been used as a dispersal field; it’s not a main bomber base, but Tu-95MS bombers have occasionally been spotted there, likely temporarily. The base’s importance lies in the few A-50 aircraft stationed there – Russia has under 10 operational A-50U in total, so each is a high-value asset.

Attack Outcome - Ivanovo-Severny: Drones targeted Ivanovo-Severny on June 1, making it one of the most daring aspects of Operation Spider’s Web – as striking an AWACS platform deep inside central Russia carries strategic weight. The Russian MoD again asserted that the attack on Ivanovo was thwarted with no damage. However, Ukrainian intelligence sources suggest otherwise: they claimed that an A-50U Mainstay was struck or at least damaged on the ground at Ivanovo. This claim, if true, would mean Ukraine managed to hit one of Russia’s “eyes in the sky,” which would be a major success. As of now, there is no conclusive OSINT imagery showing an A-50 burning (unlike the clearly documented bomber wrecks at Olenya and Belaya). It’s possible that a drone detonated near an A-50, causing some damage without destroying it outright. In early 2024, Ukraine had damaged an A-50 in Belarus using a similar drone tactic, so the SBU may have replicated that. For now, we treat the A-50 kill as unconfirmed. What is confirmed: no large fires or explosions were observed at Ivanovo by locals, suggesting any damage was limited. Russia has not paraded any A-50 with scorch marks, nor admitted to losing one (unsurprisingly). If a Mainstay was indeed hit, Russia would likely classify it as “under repair” and quietly try to fix it.

Surviving Assets - Ivanovo-Severny: Unless hard evidence emerges, we assume all A-50U aircraft at Ivanovo survived (at least structurally). Typically, 1–2 A-50s might be at Ivanovo at a given time. If one was lightly damaged, it might be out of action for weeks or months. The base does not permanently host other combat planes, so the main “survivors” in question are the AWACS and possibly a few support planes (transports or tankers) that were there. Those presumably remain – though right after the attack, unconfirmed reports suggested Russia flew one or more A-50s out of Ivanovo to safer locations (possibly further north or east) to prevent any follow-up strikes. In essence, even the attempt on Ivanovo sent a message, and Russia will be keen to safeguard these scarce assets.

Air Defense & Infrastructure - Ivanovo-Severny: Ivanovo is under the umbrella of Moscow’s layered air defenses, but again, the drones launching from close by negated much of that. If any base had robust short-range defenses, it might be one protecting AWACS; however, it appears the drones got very near. The MoD stated no damage in Ivanovo, so by their account, whatever defenses were in place worked. It’s possible electronic warfare played a role – for example, jamming the control link of FPV drones could make them crash. Without independent evidence, one can only speculate that some combination of jamming and close-range weapons protected the A-50 at the last moment. No significant infrastructure damage is known at Ivanovo-Severny. The base likely underwent a security review after June 1, given how close Ukraine came to taking out an invaluable AWACS plane. In the broader picture, an attack on an AWACS platform is strategically provocative (since AWACS are part of nuclear command and control architecture); its apparent failure helped avoid an even bigger escalation.

Other Reported Target Areas (Amur & Moscow Regions)

In addition to the four confirmed bases above, Russian sources mentioned attacks in two other regions on June 1: Amur Oblast in the Far East, and Moscow Oblast (the Voskresensk area). These references correspond to possible additional targets in Operation Spider’s Web, though details are scant:

Ukrainka Airbase (Amur Oblast): This is a major long-range aviation base in the Russian Far East (also known as Belaya (Ukrainka) near the city of Belogorsk, Amur region). It historically hosts Tu-95MS bombers of the 182nd Heavy Bomber Regiment. The Russian MoD included Amur region in the list of attacked areas, indicating that Ukrainka airfield was a target. They claimed that the attack was repelled there as well. No visual evidence has emerged from Ukrainka. Likely, either the drones for this target failed to launch or were intercepted successfully. All Tu-95MS at Ukrainka (potentially a significant number) survived unharmed. Nonetheless, the attempt demonstrates that Ukraine intended to hit virtually every base housing strategic bombers, from one end of Russia to the other.

Voskresensk (Moscow Oblast) Airfield: Russian media (and later, a Wikipedia entry with citations) reported a fifth strike attempt near Voskresensk, which is southeast of Moscow. It’s not entirely clear what facility is located here – Moscow Oblast has various minor airfields. One possibility is that this was aimed at a military transport or bomber dispersal field used in that region, or it could have been an attempt on Zhukovsky airfield (Ramenskoye) which is not far from Voskresensk and houses flight test centers. Regardless, the report suggests a truck with drones was discovered and neutralized by Russian security before it could launch, or that drones launched but were downed. Moscow Oblast’s inclusion shows the SBU was willing to strike extremely close to the Russian capital. No losses occurred in this instance. However, the psychological impact was significant – the idea that saboteurs could stage an attack within Moscow’s region caused alarm. Russia increased security at all air bases around Moscow after June 1, and no further Spider’s Web drones were reported in the area subsequently.

The table below summarizes the confirmed equipment losses inflicted by the Ukrainian strikes, based on open-source intelligence:

| Aircraft/Asset Type | Confirmed Destroyed | Confirmed Damaged | Location(s) | Details/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tu-95MS “Bear-H” strategic bomber | 8 (four at Olenya; four at Belaya) | 1 (Belaya, heavy damage) | Olenya (Murmansk); Belaya (Irkutsk) | Russia’s turboprop long-range bombers (primary carriers of Kh-101 cruise missiles). Each Tu-95MS carries up to 16 cruise missiles. Approx. 40-50 in service before attack; losses equal ~20% of that force. |

| Tu-22M3 “Backfire-C” bomber | 4 (all at Belaya) | 0 | Belaya (Irkutsk) | Supersonic medium bombers used for strikes with Kh-22/32 missiles. ~60 in service before attack. Four destroyed at Belaya were in open-ended shelters (shelters were also wrecked). No Tu-22M3 were hit at Olenya or other bases. |

| Tu-160 “Blackjack” strategic bomber | 0 | 0 | (None hit; present at Olenya unclear) | Russia’s newest nuclear-capable strategic bomber. Some had been forward-deployed to Olenya earlier, but no Tu-160 was confirmed destroyed in this operation. All Tu-160s (about 17 in service) remain accounted for after the strike. |

| A-50U “Mainstay” AWACS aircraft | 0 (unconfirmed Ukrainian claim of 1 hit) | Unknown (if hit) | Ivanovo-Severny (Ivanovo) | Airborne early-warning & control radar plane. Ukraine claims one A-50 was damaged on ground at Ivanovo, but Russia denies this and no visual proof yet. If true, it’d be the third A-50 taken out of action in 2023–25 (two were lost earlier via other means). |

| Il-78/Il-76 “Midas/Candid” tanker/transport | 0 | 0 | – | No tankers or heavy transports confirmed lost. (Initial rumors misidentified a burning An-12 as an Il-76). All Il-78M tanker planes at Dyagilevo and transports elsewhere were unharmed. |

| An-12 “Cub” transport aircraft | 1 | 0 | Olenya (Murmansk) | A four-engined turboprop transport (Cold War-era). An An-12 parked at Olenya was destroyed in the drone strike (seen burning next to Tu-95s). Likely used as a cargo support plane; its destruction was collateral but adds to the losses. |

| Airbase infrastructure (runways, fuel depots, etc.) | Minimal damage | – | Olenya, Belaya minor damage | No runways were cratered and no fuel storage areas are confirmed destroyed. Some parking aprons and at least 3 aircraft shelters at Belaya were damaged or destroyed by the blasts. These bases remain operational after repairs. |

| Air Defense systems (SAMs, radars) | 0 (no systems hit) | – | – | No SAM batteries or radars were directly struck by the drones. The operation focused on aircraft. However, the failure of systems like S-400, S-300, and Pantsir to prevent the strikes is notable. Russia has since likely redeployed additional short-range defenses to these airfields. |

Table: Confirmed material losses from the June 1, 2025 Ukrainian drone strikes, based on satellite imagery, videos, and official statements. (Destroyed = total loss or burned beyond repair; Damaged = repairable damage but out of action temporarily.)

OSINT Confirmation and Analysis of Losses

Open-source intelligence (OSINT) played a crucial role in verifying Ukraine’s claims and documenting the extent of Russian losses. In the days immediately after the strike, a variety of evidence emerged:

Satellite Imagery: Within 24–48 hours, commercial satellite companies (e.g. Planet Labs, Umbra) and private analysts obtained imagery of the affected airbases. Notably, SAR (synthetic aperture radar) imagery from Umbra was used because it can penetrate cloud cover and capture details like debris fields. OSINT analyst Chris Biggers published annotated SAR images of Belaya Airbase clearly showing multiple destroyed bombers. In those images, large aircraft silhouettes (matching Tu-95 and Tu-22M3 dimensions) are seen in wreckage, confirming that the heat signatures and fires reported were indeed from bomber aircraft. Similarly, optical satellite images (when weather permitted) showed burn marks on the tarmac at Olenya and Belaya where aircraft had been parked.

Video Evidence: Several videos from Russian locals and from Ukrainian sources captured the strikes in action. For Olenya, security camera and witness videos from Olenegorsk showed drones launching and subsequent explosions at the base. The SBU also released drone’s-eye footage of at least one target (possibly Olenya’s flightline) – this footage, later shared via The Insider and Barents Observer, shows a Ukrainian drone diving onto a Tu-95MS and a massive explosion ensuing. Frame-by-frame analysis of that video allowed identification of the aircraft types by their distinctive features (e.g., the Tu-95’s tail and wing shape). Likewise, at Belaya, local Telegram channels posted a short clip of a plume of black smoke in the distance, which corresponded to the time and location of the attack. While not as dramatic as the Olenya footage, it aligned with the satellite-confirmed damage at that base.

On-site Photos: After the fires were extinguished, a few ground-level photos leaked on Russian social media (before being removed). For instance, one image purportedly from Belaya’s apron showed the charred remains of a bomber’s tail section – though unofficial, such images corroborated the satellite observations. Russian civilians living near these bases also posted descriptions like “we heard loud blasts and saw fire over the trees,” giving credence to the event’s scale.

Independent Damage Tallies: By June 2, the independent Ukrainian OSINT group “Oko Gory” (Eye of the Mountain) and others compiled all available evidence to estimate total losses. Their assessment matched closely with the SBU’s general statements: approximately 13 aircraft confirmed destroyed (this count included 8 Tu-95MS, 4 Tu-22M3, 1 An-12) and possibly a few more damaged. This aligns with President Zelensky’s claim that about one-third of Russia’s bomber fleet was put out of action. While initially such Ukrainian claims were met with skepticism, the hard evidence from OSINT has largely validated the magnitude (if not every detail) of what Ukraine announced. For example, Zelensky’s figure of “34% of strategic bombers” likely was derived from knowing roughly how many bombers Russia has operationally and seeing ~40 hit (including non-destroyed damaged ones). As our breakdown shows, at least 8 strategic bombers (Tu-95MS) were outright destroyed – which alone is a huge blow – and additional ones are damaged or were at risk.

Russian Acknowledgment: The Russian government has been deliberately vague about the damage. In official reports, they admitted only that some aircraft caught fire at two bases. They have not shown footage of the aftermath (in contrast, when Ukrainian drones struck Engels in 2022, satellite photos emerged via Western media – but in this 2025 case, the majority of vivid evidence has come from non-Russian sources). However, the very fact that Russia’s MoD had to comment on incidents in five different regions is telling. Moreover, Russian military bloggers (unofficial but influential) have lamented the losses. Prominent pro-war bloggers described it as a “black day” for Russian aviation, akin to a Pearl Harbor moment for their Air Force. This admission in Russian online discourse, combined with the OSINT-confirmed visuals, leaves little doubt that the strike was one of the most damaging in modern history against a strategic bomber fleet.

In summary, OSINT sources have provided credible and converging evidence that Ukraine’s Spider’s Web operation achieved significant results. We can now state with confidence the minimum confirmed losses (as in the table above). As always, some ambiguity remains (especially regarding the fate of the A-50 AWACS and any minor damage at the non-primary sites), but the open-source intelligence community continues to monitor satellite passes for any signs of those assets (for instance, checking if an A-50 that was usually at Ivanovo is missing or moved). This attack will likely be studied for years, and OSINT has ensured that an accurate record – independent of either side’s propaganda – exists of what transpired on June 1, 2025.

Strategic and Doctrinal Context of the Strike

Beyond the immediate tactical success, the large-scale drone strike on Russia’s bomber bases carries far-reaching strategic and doctrinal implications for the Russia-Ukraine war – and warfare in general.

Doctrinal Frame Summary

- Russia’s strategic bombers are no longer safe in depth.

- Airbase vulnerability stems from soft perimeters, not weak SAMs.

- Nuclear signaling is now constrained by physical exposure.

- Ukraine has operationalized AI-guided sabotage at scale.

- Strategic defense now includes logistics, deception, and dispersion.

Deterrence and Escalation: Ukraine’s decision to hit targets so deep in Russia (spanning from the Moscow region to the Far East) marks a dramatic escalation in its capabilities. However, Kyiv carefully framed this operation as a defensive necessity. Ukrainian officials noted that Russia had been using these very bombers to launch frequent cruise missile barrages on Ukrainian cities in the weeks leading up to the attack. By striking the bombers on the ground, Ukraine aimed to reduce the threat of those missile attacks – effectively disarming part of Russia’s long-range arsenal. President Zelenskyy lauded the operation, emphasizing that “Ukraine is defending itself… Russia started this war, Russia must end it”. In other words, Ukraine portrayed Spider’s Web as a justified response to ongoing Russian aggression, rather than a random provocation.

This narrative is crucial because any attack on Russian soil, especially on strategic nuclear-capable bombers, raises the specter of escalation. Moscow was predictably furious: the MoD and Kremlin called the drone strikes a “terrorist act by the Kyiv regime" and vowed consequences. However, notably absent was any immediate drastic retaliation beyond increased air defenses. This suggests Russia was caught off-guard and had to first come to terms with the extent of damage.

In strategic terms, Ukraine has shown restraint by targeting military assets only – there were no civilian targets, casualties, or nuclear facilities involved, which helps limit the escalation ladder. Still, the operation undoubtedly crossed a psychological red line for Moscow: it proved that nowhere is safe, not even nuclear bomber bases deep in the Russian heartland. This could either pressure Russia towards negotiations (recognizing their vulnerability) or push them to retaliate unconventionally.

A sign of the former was that the strike coincided with tentative peace talks – Ukrainian analysts argue the timing was intended to strengthen Kyiv’s hand at the Istanbul negotiations by demonstrating its long reach. Indeed, as one observer noted, “the only way to compel Putin to take negotiations seriously is from a position of strength”. Ukraine showed strength, and any future escalation will be carefully calibrated knowing that such operations can happen again.

Impact on Russian Military Strategy: The destruction of so many bombers on the ground is a serious military setback for Russia. It immediately reduces the number of aircraft available for long-range missions (both conventional and potentially nuclear). Analysts from the West and even Russian insiders have pointed out that Russia cannot easily replace these losses – Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 production lines have been closed for decades. Each aircraft destroyed is effectively gone forever, which diminishes Russia’s force projection capability. In practical terms, Russia will have to reshuffle its remaining bombers to cover the roles of those lost. We may see fewer bombers at a time being deployed for missile strikes (to avoid grouping them as targets), or conversely, Russia might attempt a dramatic bombardment with remaining forces to “compensate” (although since the strike, there were indeed reports of a lull in bomber-launched cruise missile attacks, as Russia assessed damage and moved assets). Additionally, losing even one A-50 AWACS (if confirmed) would strain Russia’s ability to coordinate air operations, since those are crucial for detecting low-flying threats (ironically, exactly the kind of threat that took them out). Militarily, Ukraine has forced Russia to rethink its basing strategy. In the short term, Russia declared a state of emergency at unaffected bases like Engels, indicating fears of follow-up strikes. In the longer term, Russia might disperse bombers even further from Ukraine or invest in protective infrastructure.

Doctrine and Vulnerabilities: Perhaps the most significant aspect is how this operation “rewrote the rules” of what is possible in warfare with drones. Commentators have compared the strike’s conceptual impact to Pearl Harbor in 1941 – a surprise attack that changes paradigms. Just as Pearl Harbor demonstrated the reach of carrier aircraft, Operation Spider’s Web demonstrated the strategic reach of small drones and special forces. Max Boot, writing in the Washington Post, argued that this attack exposed the vulnerability of air bases worldwide – if Russia’s heavily guarded bomber bases can be hit, so can others, and traditional static defenses need to adapt. The analogy drawn was that swarms of cheap drones (costing perhaps tens of thousands in total) took out assets worth possibly $2–7 billion – flipping the cost ratio of offense vs defense dramatically. This will likely prompt a doctrinal shift: hardening of aircraft shelters (finally giving credence to those Russian voices who for years warned that parking $100 million bombers in the open was dangerous), deployment of anti-drone systems at all major bases, and an elevation of counter-sabotage efforts (screening for insider threats, securing perimeters better).

For Ukraine, this operation validates a doctrine of deep strike via unconventional means. Lacking long-range missiles (Ukraine still does not have ATACMS or similar 1000+ km missiles from allies), it found an innovative way to achieve a strategic effect. The use of SBU special forces + drones essentially created a new arm of service for Ukraine – part intelligence operation, part airstrike. We can expect Ukraine to attempt similar attacks again if the war continues, as the element of surprise can be replicated in other creative ways. On the flip side, Russia may respond by pushing for more aggressive tactics against Ukrainian leadership or infrastructure, arguing that if Ukraine can hit strategic targets in Russia, Russia might escalate its targeting in Ukraine. There were concerns raised about whether striking nuclear-capable bombers could provoke Russia to consider its nuclear posture (since bombers are part of the nuclear triad). However, there has been no explicit nuclear saber-rattling in response – indicating Russia understands these strikes in the conventional realm.

In the wider context, Operation Spider’s Web will likely enter military textbooks. It showcases how a smaller nation can level the playing field using ingenuity: by combining intelligence, subterfuge (Trojan horse trucks), and massed drones, Ukraine achieved what full-scale air raids or cruise missiles might have in the past – all without direct NATO involvement, and with deniability up until success. It sends a message to any nation relying on big, expensive military hardware: if you don’t protect your assets, determined adversaries can and will find a way to hit them. Hardened shelters, robust drone jamming, and rapid-response security units are now a must for any air force. The strike also demonstrates a form of distributed warfare – instead of one large platform delivering a massive strike, many small units coordinated to deliver a knockout punch.

Finally, strategically, this event has had a morale and propaganda effect. Ukrainians celebrated footage of Russian bombers burning, seeing it as justice for the air raids they’ve endured. Conversely, Russian military bloggers and many in the air force community were demoralized, openly calling June 1, 2025 “the most devastating attack on Russian aviation in history”. Such psychological impacts can influence decision-making and public support for the war.

In conclusion, the late May/early June 2025 drone strikes on Russia’s bomber fleet not only achieved a concrete reduction in Russia’s military capabilities, but also struck a powerful symbolic blow. They demonstrated Ukraine’s increasing sophistication and reach, challenged the effectiveness of Russia’s defenses, and heralded a new era in which low-cost drones can deliver strategic-level effects. As peace talk efforts and the war’s dynamics continue, Operation Spider’s Web will stand out as a defining moment – one that showed how innovation and audacity can shift the balance even in a high-stakes conflict.

Sources:

- Reuters – “To attack Russian air bases, Ukrainian spies hid drones in wooden sheds”, June 1, 2025.

- BBC News – “Ukraine drones strike bombers during major attack in Russia”, June 2, 2025.

- Al Jazeera – “Ukrainian drones target Russian airbases in unprecedented operation”, June 1, 2025.

- ABC News – “Ukraine targets Russian airfields in major drone attack”, June 1, 2025.

- Censor.NET (Ukraine) – “At least four Russian planes hit at Belaya airbase. Satellite image”, June 2, 2025.

- UNITED24 (Ukrainian official media) – “13 Russian Strategic Bombers Destroyed in Deep Strike”, June 2, 2025.

- The Barents Observer – “Massive drone attacks on Olenya airbase”, June 1, 2025.

- The Moscow Times – “Operation Spider’s Web: What We Know About the Drone Attack”, June 1, 2025.

- Washington Post (Op-ed by Max Boot) – “Ukraine just rewrote the rules of war”, June 1, 2025.

- EurAsian Times – “Ukraine’s FPV drones wreak havoc on RuAF”, June 1, 2025.

Related Großwald Reporting

Großwald | Defense briefings and curated intelligence on NATO’s operational architecture—linking strategy, industry, and frontline posture across Europe.